Venerating Christian Smalls Is Perfectly Fine. The Left Needs Heroes—Now More Than Ever.

One wants to avoid a Great Man theory of history, or a cult of personality. But heroes—folk or otherwise—are an essential part of successful mass movements.

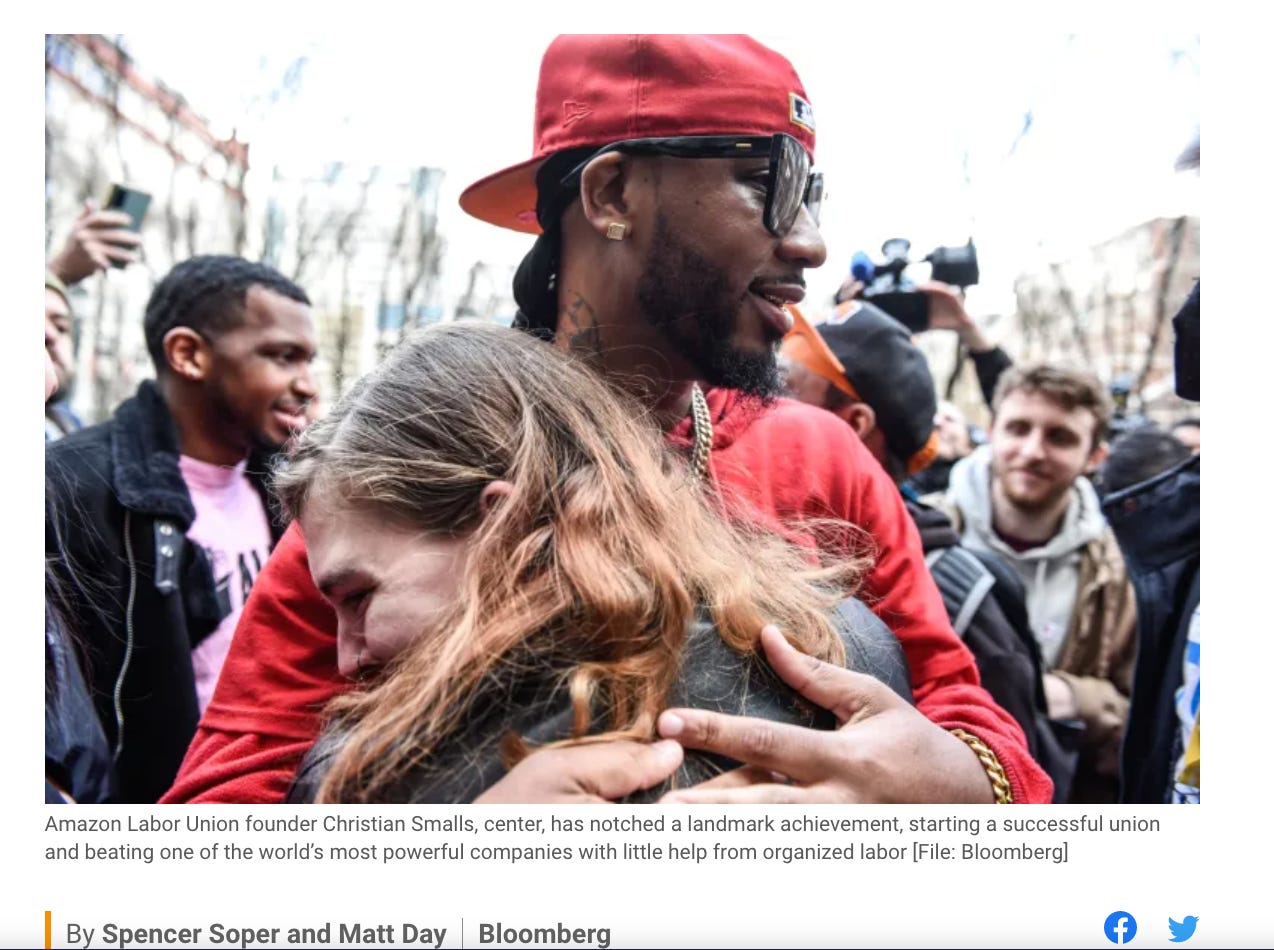

Amazon warehouse workers in Staten Island, New York stunned the world this week when they voted 2,654 to 2,131 (out of 8,325 eligible voters, with 67 challenged ballots) in favor joining Amazon Labor Union, making them the very first to unionize at the massive company, which is known for its vicious anti-union campaigns. The election at the JFK8 fulfillment center, which was supervised by the National Labor relations Board, was immediately followed by jubilant celebration: Images of workers hugging, cheering, crying, and popping champagne bottles instantly flooded the internet.

“We want to thank Jeff Bezos for going to space, because while he was up there we were organizing a union,” ALU President Chris Smalls proclaimed to a crowd of workers, reporters, and supporters, just after the results were revealed, as journalist Lauren Kaori Gurley documented. The victory was extra triumphant because Smalls had been fired by Amazon two years prior for leading a protest against unsafe working conditions during the pandemic. According to leaked notes obtained by journalist Paul Blest, Amazon executives had internally discussed a plan to smear Smalls, and they referred to him as "not smart or articulate." After he was fired, Smalls went on to found the ALU, the scrappy, independent union that would go on to win this historic union election. As journalist Luis Feliz Leon wrote of the victory, “It’s the magical stuff of Disney movies.”

Subsequently, a moderate debate has stirred around how much credit or publicity to give to Smalls. Without getting too much into the weeds of the Online Discourse, I wanted to say a few things about heroes—something I’ve been thinking a lot about for the past few years.

In 2007, arch neoliberal and plebeian-nudger Cass Sunstein coined the term “Goldstein Effect” in reference to Emmanuel Goldstein, the shadowy Official Enemy from 1984. The "Goldstein effect," according to Sunstein, has "the ability to intensify public concern by giving a definite face to the adversary, specifying a human source of the underlying threat." Put simply, like with Osama bin Laden or Saddam Hussein, the state needs an enemy face to marshal public support. One of the primary problems, Sunstein argued, with getting the public to care about climate change is that there was no face, no name, no major villain. Humans, he argued, are innately drawn to personalities more than causes, and if the former could contain and personify the latter, it has a much better chance of stoking the requisite human emotions to compel change.

While Sunstein’s application could have cynical implications, I’ve long thought his broader point is true. And the inverse is also true: Causes need human faces—heroes we can be inspired by and see ourselves being. This isn’t inherently a good thing: Pop culture with bad politics has created hundreds of dubious heros. Cop and military shows, studies show, unduly influence real-life abusers in law enforcement. The West Wing, with its romantic vision of End of History smug liberal tinkering spawned thousands of dead-eyed Georgetown grads who wanted to cosplay as Josh or C.J. in Washington, but never developed politics beyond “if the New York Times editorial board says it, it must be true.” But this is an issue of structural problems with cultural production under capitalism, not with the concept of heroism as a rallying device.

The totality of pop culture depictions of heroic union organizers could be counted on one hand, Boots Riley’s wonderful “Sorry to Bother You” being a somewhat recent member of a very small club. Thus, labor cannot turn to pop culture for its heroes—more often than not, when unions do appear, they are juiced for salacious mob stories. Given the media corporations that fund film and TV, the ratio of Heroic Cop to Heroic Labor Organizer will likely remain 10,000 to 1 for the foreseeable future. So, those on the business end of labor abuse—the millions of Americans who are teachers, waiters, farmworkers, or suffer the indignities of working for Amazon, Walmart, Kroger, and Uber—don’t have pop figures to look up to, or to see themselves in.

This is why I see the veneration over the past few days of Smalls as not only healthy, but long overdue. The Left has someone who was harassed, abused, cast out, and subject to racist abuse by Amazon’s sleazy pinkertons. He rose from the ashes and led—alongside many other workers—a historic win over arguably the most powerful corporation in the world.

Cheering and praising Smalls’ act of courage doesn’t take away from the no-doubt countless hours his co-conspirators put in to make the unionizing effort possible. (Wonderful breakdowns of this collective organizing effort can be read here and here.) In the 1910s, when the Industrial Workers of the World sent Elizabeth Gurley Flynn or Big Bill Haywood or Joe Hill to attend a picket line to inspire strikers with speeches and songs, no one thought this, in any way, took from the unseen labor organizers. They were treated like celebrities, but celebrities for a noble cause, playing the necessary—if unseemly—game of public relations. It was propaganda, good media, and they knew this was important. No one was precious about some meta-implication that this somehow erased others in the struggle. It’s an innate part of the human condition to put a face to a movement. Indeed, most successful movements have had charismatic leaders, because humans are social mammals who love seeing themselves in others.

Obviously one wants to avoid hero worship. This is a point that Smalls has reportedly made himself, according to journalist Luis Feliz Leon, who wrote on Twitter, “Chris Smalls is a charismatic leader, but he himself has told me that it was the work of the 20+ organizing committee that pulled off today's victory. Americans' obsession with individualism shouldn't change that narrative.” This is an invitation to be cautious of the potential pitfalls of hero narratives—one being the real danger that the collective character of the struggle will be erased, which would be a disservice to this and future union organizing efforts. After all, large numbers of workers toiling in obscurity, doing the unglamorous work of turnout calls and door knocking and outreach, is the engine of any union drive.

But I don’t read this note of caution as a dismissal of the concept of heroism. Rather, we can draw those circles of heroism wider—celebrate the righteous victory of Chris Smalls, and also of JFK8 packer Angelika Maldonado, the chair of ALU's Workers committee, who shared fascinating insights into how the union drive was successful. Or Smalls’ best friend, Derrick Palmer. Or ALU member Justine Medina, who was recruited as a salt and tells of workers studying communist organizer William Z. Foster’s Organizing Methods in the Steel Industry. The thing about popular labor heroes is we need more of them, not less. And at the JFK8 warehouse in Staten Island, there is no shortage of them to go around. Celebrating Chris Smalls does not foreclose on lifting up other heroes of this fight. Let’s celebrate them all!

Politicians, as useful and nice-hearted as they may be, cannot serve the function of hero. Bernie Sanders developed a bit of a cult of personality in both of his presidential runs, and he brought many into left politics, popularizing a certain brand of class anger that no doubt has helped build the ranks of socialist movements. And while some politicians can, and historically have, had a positive effect on pushing important causes and legislation, they are still responding to grassroots movements, not leading them. Or, at least, this is how it should be: In an ideal scenario, a large and sophisticated Left would have the strength and organization to discipline politicians, keep them in line, and create real consequences when they betray social movements. Venerating those in positions of power—which, no matter how much one may like an elected, is what they are—isn’t looking to a hero for inspiration, it’s looking to the system as salvation. Politicians can be allies, they can be liked, but a hero they can never be. And that’s fine: It’s not their function.

Smalls’ story, however, is both organic and an inspiration to everyone who’s been treated like shit by their boss, humiliated, gaslit, subjected to racist condescension. Put simply: He’s an avatar for the average American wage worker in 2022, who cannot, by definition of living in a capitalist cultural economy, turn on a film or TV show and see heroes sticking it to their boss, outside the occasional, depoliticized revenge fantasy. He’s a textbook folk hero, who, if he can help rally Amazon workers throughout the country to duplicate the success of the Staten Island workers, could encourage countless others to step up and become heroes themselves. And if he can do this—advance the highest of moral duties: unionize workers—then I say three cheers for the Legend of Christian Smalls.