U.S. Media’s Bogus ‘Worker Shortage’ Stories From Last Spring Predictably Helps Throw Millions Into Poverty

Anti-poor Republicans and feckless Democrats are to blame, but so is American media, which uncritically disseminated Chamber of Commerce talking points for months.

One thing that can be difficult in media criticism is conveying the stakes. Beyond the dunking on hypocrites, the gotchas, the pointing out conflicts of interests, and the double standards lies very real, human stakes. After all, all that sophistry and slick P.R. framing pushed out by corporations, billionaires, and governments exists for a reason. And that reason, more often than not, is about transferring wealth and political power from the poor to the rich. It’s rarely more complicated than this.

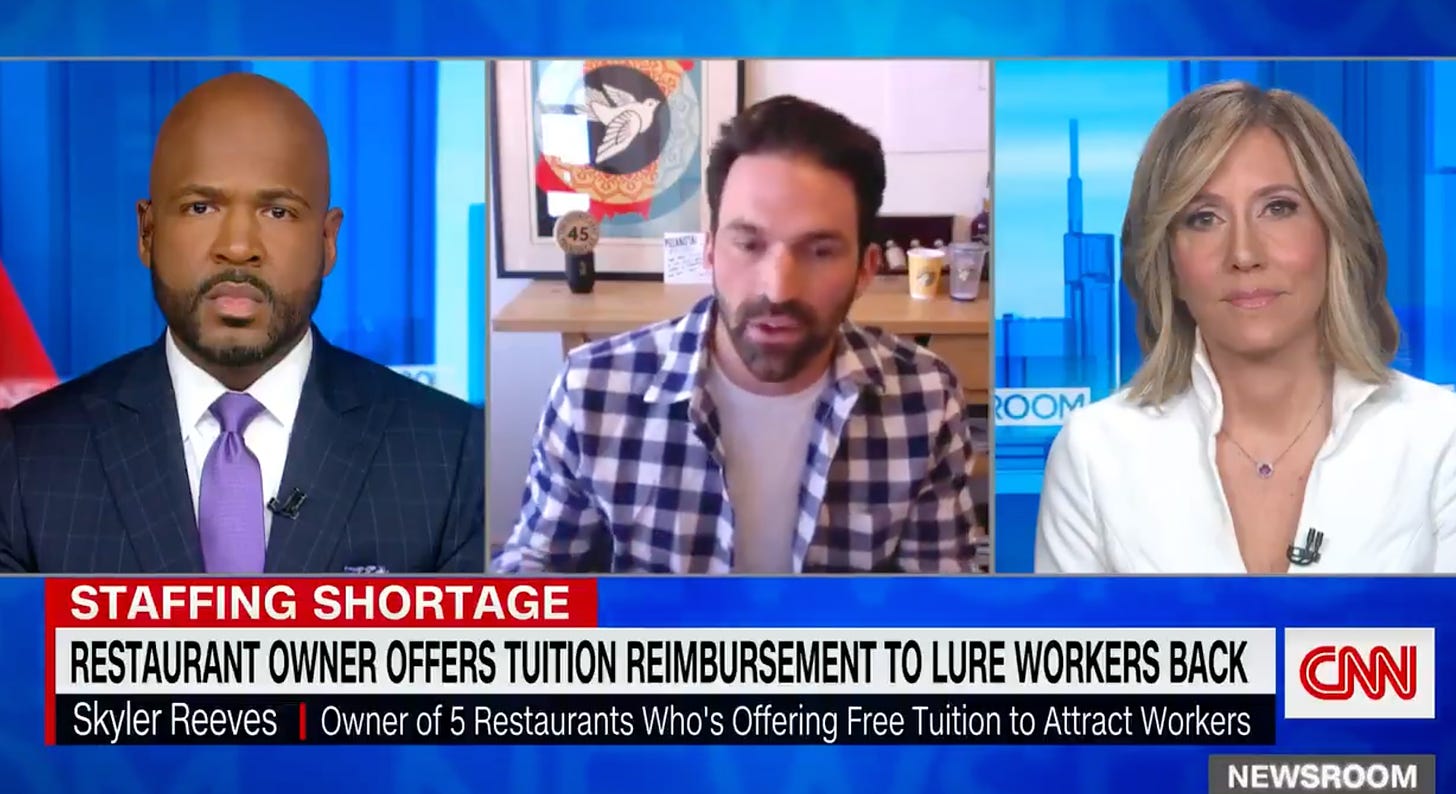

It’s not often, however, that one is presented with a media malfeasance story that is this clear and bleak. Monday, September 6, federal supplemental unemployment insurance (UI) is ending for 9.3 million Americans—affecting some 35 million people living in a household dependent on the benefit. This, on top of the end of the federal eviction moratorium, and dozens of states stopping their separate UI programs, has created a perfect storm of mass suffering. Some are calling this “the benefits cliff”—effectively throwing millions into poverty overnight. And for an assortment of reasons that would require a whole other post to dissect, there’s been almost no effort by Democratic leadership or the White House to prevent it.

One of the, if not the, key pillars justifying the ending of these benefits has been the idea that UI has created a so-called “worker shortage” for employers and hampered recovery. Despite the fact that this premise has been debunked by countless economists and writers, it was quickly cemented as conventional wisdom in April and May of this year, pushed out by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other industry groups and business trade organizations, and uncritically repeated as per-se a problem with little critical examination of the basic premises.

We know the torrent of “worker shortage” stories is the product of lobbying by business interests groups because the sources being cited, in addition to the Chamber of Commerce directly, are trade groups hand picking certain media-friendly business owners (we traced this pattern in an April episode of my podcast Citations Needed). Reporters, for the most part, didn’t just magically sense these otherwise obscure employers were “struggling to find workers”: They were put in touch with sympathetic businesses by a third party—almost certainly local and national Chambers of Commerce and other restaurant associations. As such, this perspective was privileged and allowed to shape the narrative.

After all, poor people, unlike business owners, don’t have multimillion dollar lobbyists and trade groups to pitch and shape stories for reporters.

But the basic premise was faulty, if not—to put it mildly—contestable. The idea that the problem was low wages offered by stubborn, cheapskate owners was either ignored entirely or quickly hand-waved away. Last spring, American media outlets, with very little pushback, did P.R. work for what was effectively an informal capital strike on the part of businesses dependent on low wages. These firms (correctly, it turns out) wagered it was in their long-term interests to aggressively lobby and push for gutting UI rather than meeting wage demands of workers, which could set a precedent in the coming years, if not decades.

And, right on cue, major outlets simply accepted the “labor shortage” premise. But as Forbes Senior Education correspondent Peter Greene wrote in 2019, in the midst of another so-called “labor shortage” panic specific to teachers, this framework is the absolutely wrong way for our media to look at mismatches in wages offered versus those accepted. He wrote:

You can’t solve a problem starting with the wrong diagnosis. If I can’t buy a Porsche for $1.98, that doesn’t mean there’s an automobile shortage. If I can’t get a fine dining meal for a buck, that doesn’t mean there’s a food shortage. And if appropriately skilled humans don’t want to work for me under the conditions I’ve set, that doesn’t mean there’s a human shortage

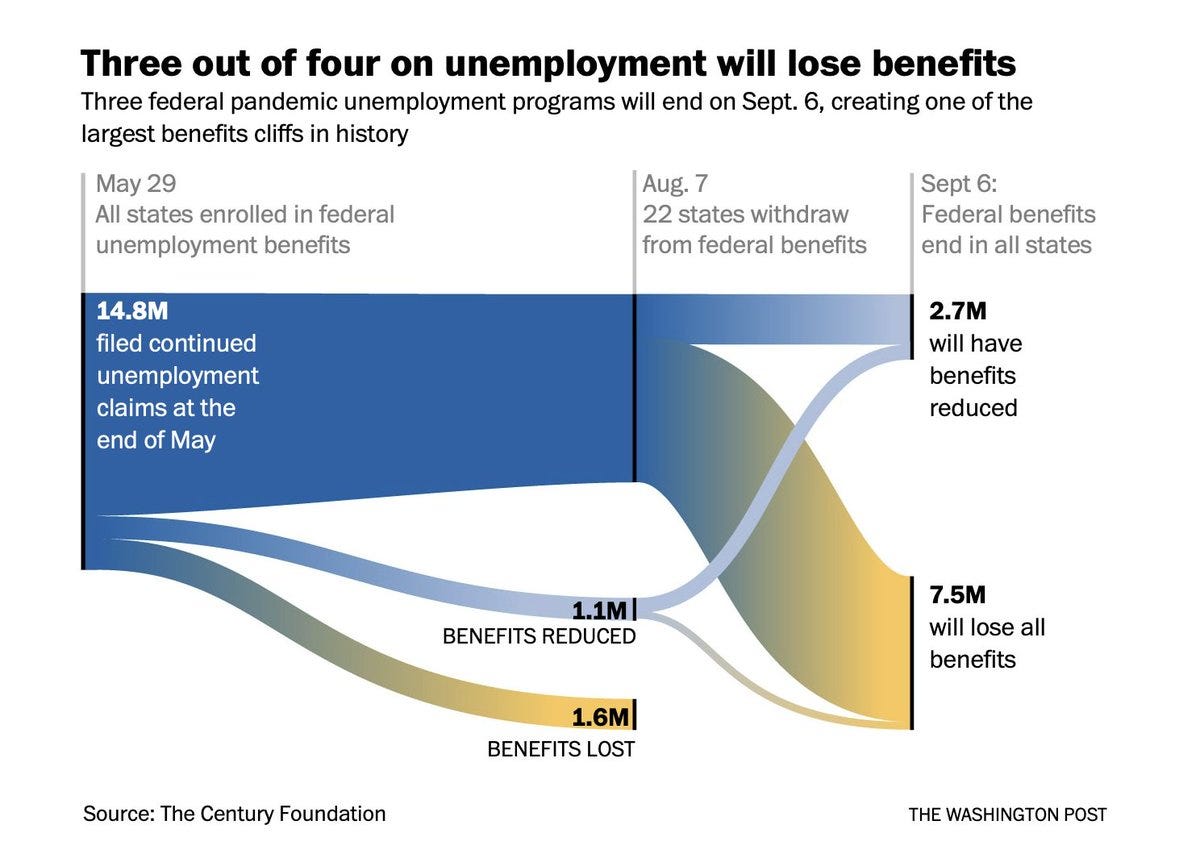

As such, the basic problem of a lack of sufficient wages—wages that have plummeted in real terms in the past few decades (see chart below)—was glossed over altogether, and what the public was left with was literally thousands of stories sourced primarily from the Chamber of Commerce painting a picture of layabout workers and employers forced to shut down or close as a result.

Let’s examine three cases of these Big Business talking points that were uncritically disseminated by U.S. media: two from CNN and one from NPR. There are, as we noted, countless other examples, but for the purposes of the survey we will drill down on these three.

First, we have a breezy afternoon CNN show with Poppy Harlow and Victor Blackwell from early May teeing up a segment with “Arizona restaurant owner” Skyler Reeves by insisting business owners are so desperate they’ve tried everything from “new incentives, including bonuses, wage increases, and sign on bonuses.” But then, the segment moves on to discuss any solutions but increased wages. And by and large, the businesses featured complaining on the segment had refused to meaningfully increase wages. They did, however, come up with gimmicks that got them on TV to promote their real objective: lobbying against supplemental state and federal unemployment insurance:

Notice how Reeves, owner of the Vivili Restaurant group, immediately gets to his talking points arguing why pandemic aid should be cut. This is the real objective of the segment—the free college line is a red herring.

If one goes to the Yavapai Community College website and examines the fine print it’s clear that for any employee to exploit this “free tuition” they have to work at the restaurant for three months before they become eligible, then work at least 30 hours a week at the restaurant every week while attending school, enroll in at least 32 hours a week of classes, and have a “passing grade of C or better to receive the reimbursement.” So, one is expected to enroll on the hopes that they can balance a 60+-hour work/school week, not let their grades slip, all while hoping their employer—who is ostensibly on the hook for paying their tuition if they succeed—doesn’t fire them or reduce their hours below 32 a week. If they fail to meet these criteria, they’re out the whole of the college tuition.

The Column reached out to the Vivili Restaurant group inquiring how many employees, four months on, have had their tuition costs paid for. As of publishing, we have not received an answer but will update this post when we do.

A much more elegant way of attracting workers is to simply increase wages by a meaningful amount. Instead, employers are more interested in spouting patronizing “bootstrap” gimmicks about “free tuition” in order to get on TV, with the primary goal of having a forum to argue against UI and, maybe, enticing workers as an incidental perk of the media appearance.

The previous day, NPR ran one of many credulous “labor shortage” stories about employers unable to lure workers to work for them. In “Hotels And Restaurants That Survived Pandemic Face New Challenge: Staffing Shortages,” Tovia Smith entirely centers business owners, even populating the piece with a Very Sad picture of the owner having to engage in the indignity of washing dishes.

One anonymous “worker” is handpicked for comment and sounds like a John Stossel parody of a welfare queen:

Why would you expose yourself to the risks of working in close quarters, serving people food and drinks, when you could just make more money on unemployment?" says one longtime restaurant employee, who asked that his name not be used, for fear of hurting his future employment prospects.

"Sometimes it's not really worth the money that you get, when you're leaving [work] at 3 in the morning, worn out, tired and sticky," he says. "You know, like, I make enough staying home."

This “longtime restaurant employee” makes no mention of higher wages which, again, is the key issue at work here. But wages are hand-waved, with this throw-away paragraph:

In resort areas such as Cape Cod, however, businesses say they're offering around $20 an hour for midlevel kitchen jobs, for example. U.S. Rep. Bill Keating, D-Mass., who represents Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket, also disputes the notion that low wages are the issue. Staffing shortages are a perennial challenge, he says, but with as much as one-fifth of the hospitality industry already fallen victim to the pandemic, the stakes are especially high this year.

So, seasonal jobs always have trouble finding workers because it’s seasonal and living in Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket is extremely expensive. NPR doesn’t follow up by asking difficult questions to the owners, such as: Why not pay $25 an hour? Why not $28 an hour? Instead, as it is the case with all these stories, the idea of higher wages is touched on but dismissed as a non sequitur.

There’s one token quote from a progressive think tank pushing back on the basic premise of the piece, but this is completely undermined in the next paragraph, which tells the reader higher wages really don’t matter. All the main talking points are there: Supplemental UI is making workers lazy, it’s effectively shutting down the economy, and owners simply cannot afford to compete with government aid and cannot afford higher wages.

Again, NPR has run dozens of these stories over the past year. In fact, the outlet was one of the earliest, publishing an April 2020 sob story for a Kentucky Coffee shop owner who had a difficult time finding workers as the pandemic raged and tore through poor communities. This piece, roundly criticized at the time, set the template for all that followed: center then needs of a “small business owner,” blame UI, cite the Chamber of Commerce (not disclosed by NPR, the coffee shop owner’s husband was the head of Harlan County Chamber of Commerce), and gloss over the lack of increased wages entirely.

What makes NPR’s wholesale adoption of this trope uniquely problematic is that its listeners are the exact demographic needed to erode support for pandemic aid: wealthy liberals who make up much of the decision making apparatus of the Democratic Party on both a state and local level. Stories about lazy workers sucking on the government tit are to be expected—and likely don’t change much politically—when running on Fox News or the New York Post. But in liberal-leaning media they carry tremendous political consequence, as evidenced by Democrats' wholesale abandonment of the pandemic aid.

Our final example is a rather risible segment on CNN from July about the CEO of a solar panel installation company being forced to install his own panels:

What makes this segment fascinating to watch is that the owner undermines the whole premise of the piece by casually mentioning he cracked the code of ending the labor shortage: He decided to pay people more:

It turns out, not a lot of people wanted to make $38,000 a year working in 100 degree weather at a job where, if they trip, they stumble to their untimely death. But, if the salary is bumped up to $50,000 or $65,000, people will consider it. Not mentioned by CNN is that roofing (which is essentially what the job is) is one of the most dangerous jobs in the United States, with a fatality rate of 38.7 per 100,000 workers—three times that of police officers who get their own protected class status due to the alleged danger of their profession. The injustice here, according to CNN, is not that this business owner isn’t paying employees enough for an incredibly hazardous job—it’s that the poor CEO has to actually do the work himself because he refuses to raise wages.

Again, for the past year we’ve gotten the exact same “worker shortage” story from CNN over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over again. There were a handful of dissenting takes, but these were relegated to online articles, not segments actually airing on TV (e.g. the thing that actually matters.)

It’s impossible to know how much the American press’s largely uncritical embrace of the “labor shortage” narrative led us to this point—measuring media impact is always difficult. But these stories do not exist in a political vacuum, and helped normalize and make bipartisan the primary argument for throwing millions off one of the most effective forms of social welfare we’ve seen in decades—providing cover for Republican governors from the jump. Public and policymaker support for gutting anti-poverty measures doesn’t emerge from nothing. Those who mindlessly pushed a simplistic tale of UI making workers lazy and employers bankrupt should understand that their coverage has consequences. Large media outlets play with live ammunition, and in the coming weeks, as we no doubt see a rise in poverty and hunger, the human costs of the “labor shortage” trope will become both bleak and obvious.

Great story. You mentioned NPR not saying the KY boss’s husband ran the local CoC. I think part of the problem is that most Americans don’t see the CoC as an incredibly conservative lobbying group. They just think it’s a bunch of local business owners promoting small biz. That gives these guys tremendous leeway to manipulate the media.

This is a great piece. Great work, Adam!