The Siren Song of ‘Gen Z’ Political Branding

That a candidate is young is modestly interesting, but it’s not—in and of itself—a mode of politics, much less change.

A recent ad announcing his intent to run for Texas’ 18th district—and subsequent massive fundraising haul—shined a media light on “Gen Z” Isaiah Martin. Some responded positively, welcoming Martin’s somewhat vague message that focused on his youth and “defending democracy,” but many online mocked the seemingly vacuous message in his launch. Martin’s “issues” page was notably sparse (and later deleted altogether) on Big Ticket progressive items like Medicare of All and Climate change policy. In the “First Bills to Co-Sponsor” section of his campaign site, Martin listed a congressional resolution titled “Recognizing Israel as America’s Legitimate Democratic Ally”—not particularly a priority for progressives who increasingly oppose Israel’s apartheid regime.

As Prem Thakker noted at The Intercept, despite Martin’s pitch as a fresh-faced “Gen Z” politician, his political priorities don’t align with those of Gen Z. And it’s not as if Martin’s relatively conservative politics are some unfortunate political necessity. His district went in the Biden column in 2020 by 3-to-1. And the seat’s current occupant, Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (who is running for mayor of Houston but may still retain the seat), won re-election at a roughly 45-point margin. This is not a Machin-type excuse situation of “we have no choice but to dump on progressive policies, to win over a moderate district.” This is a For the Love of the Game situation. Or, at the very least, a love of big monied corporate and AIPAC donors.

“Poll after poll has shown that young people care most about bold climate action, Medicare for All, and other progressive policies,” Aidan Kohn-Murphy and Elise Joshi of the political advocacy group Gen-Z for Change told The Intercept.

While this is true (polling overwhelmingly shows younger Democrats support more rights-based, robust policy solutions) I think using this as a proxy for what politics those claiming the “Gen Z” label misses the point a bit. The Isaiah Martin affair could be an opportunity to have a bigger discussion about where this type of Generations framing gets us—which I would argue is not that far, and carries risks that may not make this brand of politics worth preserving.

That certain cohorts based on an arbitrary window of when they were born share certain political priorities makes sense on its face. Obviously, a 20 year old will feel the impact of catastrophic climate change, for example, more than, say, a 90 year old. But a white 20 year old, statistically, doesn’t have a lot in common, inherently, with a black 20 year old in terms of health and economic outcomes. A poor 20 year old doesn't have a lot in common, inherently, with a wealthy 20 year old in terms of health and economic outcomes. A queer 20 year old is subject to different forces of discrimination than a non queer 20 year old. A 20 year old woman will suffer different modes of oppression than a man. Generations are a cohort, yes, but they only become useful once one accounts for more meaningful vectors of oppression—class, white supremacy, sexism, anti-LBGTQ currents. And once one qualifies for these other vectors, what’s left is something, but it’s not a lot.

The idea that that which is youthful is fun and exciting, and that which is old is lame and boring, is a truism as old as advertising. America’s political leadership is, indeed, as old as the wind, but the antidote to this can’t be to use “youth”—in and of itself—as a proxy for something different and exciting. Indeed, this was the primary, and in key ways only, pitch used by some of the US and Britain's most destructive anti-Left politicians of the last 40 years. Bill Clinton’s “third way” New Democrats sold the then-44-year-old Arkansas governor as they did Pepsi, Generation Next. So did then-43-year-old Tony Blair’s handlers when taking on the supposedly old, stoggy Labor Party, which is to say a Labor Party that had ideological fidelity to Labor (so lame and dusty, right?). Then-41-year-old Obama leaned heavily into this dynamic while selling a kinder gentler version of the same neoliberal policies as Clinton. Pete Buttigieg—and the scores of dead-eyed Buttigieg clones currently polishing their resumes and plotting at Georgetown mixers lining up behind him—will no doubt use this same narrative to justify their campaign: a new voice, new face, young, fresh, energetic, new ideas, blah blah. But in the end, none of it really means much.

Then there’s the corollary problem that our electeds’ various youthful identities don’t predict their politics. How many young, upcoming conservatives in Congress have been found out to be outright fascist weirdos? “I’m Trump but 38” is basically the entire pitch of current GOP primary candidate Vivek Ramaswamy. They’re not a majority, but this framing is so infinitely exploitable it could be used for just about any mode of politics.

One major problem, I argue, is that the causality is backwards. The forces of capital and conservatism often make our lawmakers old, not the other way around.

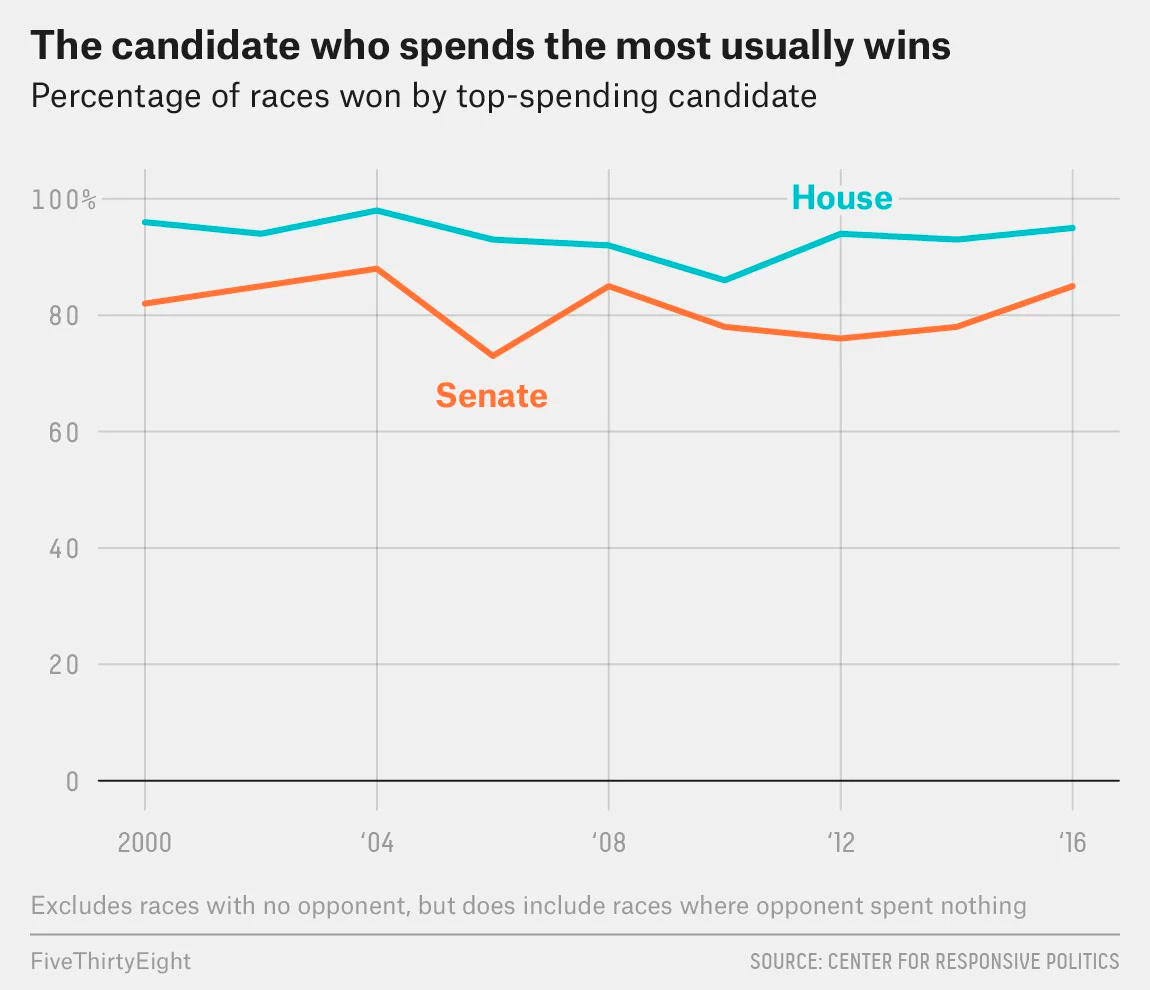

What do I mean by this? Politicians who don’t buck power, who don’t take on Corporate America, don’t upset AIPAC, don’t ruffle too many feathers, by definition, will raise more money, are less likely to have well-funded opponents, face less primary challenges, and survive longer. Ilhan Omar (M-5), for example, had to spend $5.6 million in 2020 and $3.1 million in 2022 just to hold on to her seat, despite being very popular, because AIPAC and rightwing billionaires find a new zombie millennial to throw at her every two years. It’s therefore understandable why the average politics-watcher would then equate age with conservatism: They do correlate, but not always for reasons that it may seem. A similar theory has been floated explaining why the voting base writ large is more likely to be conservative as it ages: the rich and white are more likely to be conservative and the rich and white are simply more likely to survive. It doesn’t explain all of the predictive power of age and reactionary politics (sometimes people just grow into petit bourgeois sell-outs, clearly) but it does explain some of it, and it’s a dynamic that I think plays out in the halls of American politics where principled, populist electeds or would be-electeds are routinely weeded out by the profound evolutionary force of our legalized system of bribery.

One topic where I think Generations Politics can be useful is Climate Change, the issue of issues, but even here there are limits and examples of how it can cover for the real authors of our oppression.

A viral video in 2019 of a then-86-year-old Diane Fienstein telling a dozen minor climate activists to eat shit, understandably, reinforced the narrative of out of touch old electeds:

But here, too, age discourse risks obscuring more than it elucidates. It’s true, in an abstract sense, that old people have less to lose if the Earth boils. But also elderly people typically do have children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and there’s no reason to think, on an institutional level, they’re sociopaths indifferent to their progeny’s deaths, if only for selfish biological reasons. Dismissing (the now deceased) Feinstein as old and moving on avoided more material—and perhaps more useful—motives behind her outburst. As Branko Marcetic noted in his investigation for In These Times, “Feinstein, whose net worth stands at $58.5 million, has been married for nearly 40 years to Richard C. Blum, a wealthy investor who still runs the private equity firm… According to Feinstein’s most recent financial annual report, filed in May 2018 and covering the 2017 calendar year, Blum owns 100 percent of Yosemite Investments LLC, through which he has hundreds of thousands of dollars invested in several fossil fuel companies, some of which he has sold off since the Green New Deal began gaining increasing national attention.”

The piece would go on to detail Feinstein and Blum’s investments in a mutual fund run by the investment firm of a large methanol producer, a mining company, coal, natural gas and natural gas liquids production and oil sands projects.

Isn’t this a far more useful framing—the fact that our country is run by venal rich people heavily invested in profiting off destroying the earth—than squishy think pieces about how “older people should listen to the young”? Is there some inherent tension between older and younger people in how urgently they view the climate crisis? Almost certainly. But also, sitting lawmakers and their partners shouldn’t be heavily invested in fossil fuels. And isn’t the latter more material and actionable than nonprofit-ese about “listening” to a vague cohort of “young” people, whatever this means.

But we can discuss both, one may respond. We can discuss the problem of the olds and the venality. Except the problem is we didn’t: Virtually all of the responses to the Feinstein episode centered on the age question. Which is exactly what our multimillionaire electeds want us to focus on, because it’s far less subversive than discussing the institutional, rampant conflict of interests in Congress from campaign financing to stock trading. This is what I mean when I say Generations Politics can obscure more than elucidate, it often takes up oxygen that could be used on more substantive critiques.

When I’ve brought up this criticism of Generations Politics before, it’s been met with genuine anger from some quarters. People of various ages have an emotional attachment to the narrative of Young vs. Old that strikes me as way out of whack with the usefulness and subversive potential as the framework. If Elon Musk, David Gergen, Dave Portnoy, and Tucker Carlson use the line, how useful could it be?

Well, obviously a politician has to have good politics, but they also should be young. Young people need representation in Congress. I don’t disagree with this. To the extent reasonable, Congress should reflect the demographics of the population. But being young, as Aidan Kohn-Murphy and Elise Joshi of Gen-Z for Change note, isn't a sufficient reason to run for office. Good politics matter first and foremost. But once one accounts for good politics, it’s not clear to me how youth, as such, becomes a meaningful selling point. And if it is, to what extent has it had such a class-flattening, Vibes-Only effect on political narratives that it isn’t a mode of politics worth preserving? How many more young Trump clones, or AIPAC-courting 26-year-old careerists are going to sneak through the door of Generations Politics before we decide to de-emphasize it, or at least heavily qualify it? The Next, Big, Up-and-Coming thing is a Madison Avenue angle as old as PR. If used for good I don’t mind it, but lately it seems it’s used, far more often, to sell the same monied, pro-corporate and stale politics that got us into this mess. And this geriatric millennial thinks, somewhat self-interestedly, that maybe we shouldn’t traffic in this narrative more than minimally necessary.