After Uvalde, “Police Lie” Should Be the Default Position

No institutions lie more consistently, with less pushback, than police departments. Perhaps after the latest high-profile police narrative falls apart, our media can reexamine its default stenography.

I’ve been hesitant to comment on the Uvalde shooting because I think, as Jay Caspian Kang points out today in the New York Times, there is very little anymore to add of value to what is, at this point, an entirely predictable media cycle, or what he calls “The Museum of Unbearable Sorrow.” In the Take Economy, there’s incentive to say something on major events, just to say something—The Pundit’s Curse, as I call it—and one I aggressively try to avoid. Especially the vulgar instinct to shoehorn one’s own ideological hobbyhorse into whatever tragedy is unfolding at the time. That is, unless one’s ideological hobbyhorse is entirely relevant to the discourse at hand. Then an intervention seems both sensible and useful.

As such, I think this could be a watershed moment in the broad media practice of default credulity with respect to police claims—a widespread and institutional practice. While there was a bit of mainstream pushback after the George Floyd protests, now that we’re in the post-Black Lives Matter media environment of pro-police Liberal Reaction, this current has mostly faded.

Watching recent reports of police claims dissolve and Texas officials fumble over basic contradictions in their story, I do think something meaningful can be said about the essential nature of the media-police relationship. For over 24 hours, police claimed they had “engaged” the shooter in a firefight. This turned out to not be true. Police said he had on body armor. This turned out to not be true. Basically, none of the most important details about their initial story turned out to be true.

What’s important to understand is that this is entirely par for course. The default assumption any time police make a claim should be that they are lying. Not that they could be lying, or that they may have incomplete information, or that they’re good-faith confused, but that they are doing what they all do: covering their ass, protecting their own, and, as is often the case, lying to achieve both of these ends. This is their ethos and always has been. Police lie as a rule, not now and then, not only in certain circumstances. Institutionally and by default, they obscure, bullshit, make things up, victim-blame, and deceive. Because they know they can and, even if they are caught, there is zero institutional pushback or consequence from either city officials or the media.

If a reporter, news magazine, or any other government agency (outside the Pentagon or other militarized sectors of our society) were caught lying this often, they would be discredited, fired, removed from power, and shamed. But police departments rarely suffer any such fate. They don’t even offer a scapegoat. They just… move on.

Who was disciplined for the grotesque police lies following the police shooting of Walter Scott in South Carolina in 2015, that were only debunked because someone took a video? Who was discipled when the Department of Justice determined the Chicago Police Department has a pattern of lying and concealing evidence? Who was put on the hot seat when the New York Police Department asserted, without evidence, that bail reform and releases from Riker’s Island in the middle of a pandemic were driving a surge in shootings? When they lied about “outside agitators”? When they doxxed a mayor’s daughter? Who was disciplined for the cruel police lies involving Eric Garner’s killing in 2014 that were only debunked because someone took a video?

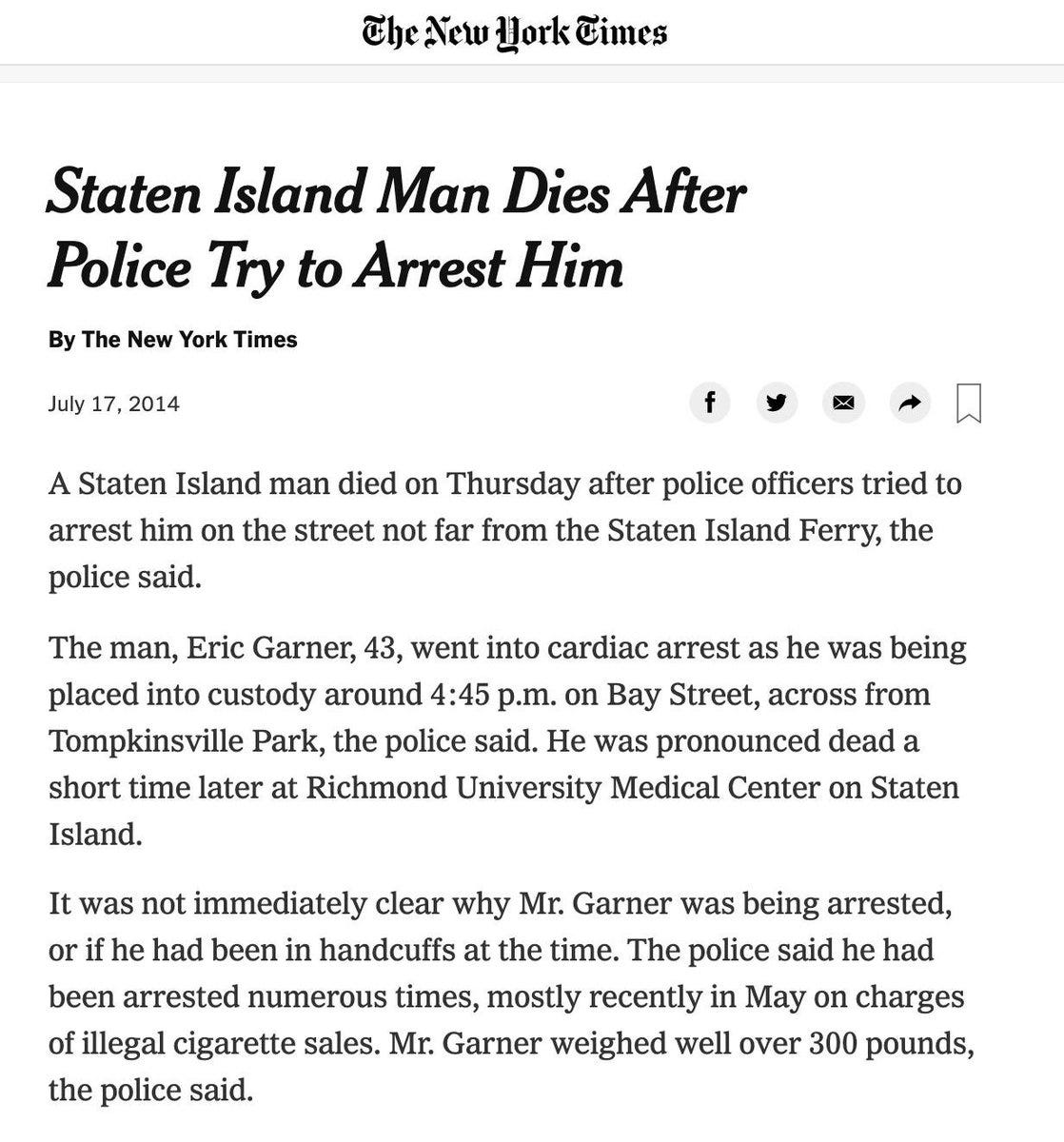

Indeed, let’s look at the original New York Times report on Garner’s death, complete with “police say” victim blaming.

“Mr. Garner weighed well over 300 pounds.”

Much of the practice of running with police narratives is a product of the nature of how our information distribution works. Police have access to “official accounts,” crime scenes, arrest reports—they have a virtual monopoly on information, which is the currency of “news.” As such, they are largely viewed as neutral entities simply calling balls and strikes and “informing” the public. While this is not true in general, it’s especially not true when they’re reporting on themselves. And, as Uvalde shooting spin shows, the working assumption should be that their press conferences, leaks, and reports are designed to do one thing and one thing only: cover their ass. And, to the extent they need to “update” their account of events, it’s only when pressured to do so. In the case of Uvalde, given how high-stakes it is and how documented the events were, this process of “clarification” is largely playing out. But think of the tens of thousands of interactions not caught on tape, not subject to this much press scrutiny—the everyday “police say” “the suspect” “fled” “with a deadly weapon” blogger-speak that is simply repeated word-for-word in local news thousands of times a day. It shouldn’t take the collective anger of survivors of a mass shooting to compel this type of follow up: It should be the default state of media. But, as we see time and again, it’s not—regardless of how much police departments institutionally lie.